Category: General

Seven Years – or thereabouts

In January I will have been at the Wikimedia Foundation for 7 years. 1 My role has changed a lot over those seven years, as has the organization and the wider Wikimedia movement. At the end of this year, I wanted to take a second to write down what I do and why. This is a pseudo-introduction post for social media (where I don’t have much of a presence) and a chance to pen a, “What I do for a living” blog post.

One of the big things I do is help with movement-facing communications stuff for the Wikimedia Foundation. The non-profit that supports Wikipedia and other free-knowledge projects. My job is to get teams at the Foundation to talk to the volunteers and share what they’re doing. Lots of behind-the-scenes feedback and input on how to find folks and where to talk to them – before we go and talk to them!

That’s always ongoing, never ending work that most of the time works well. Teams write their thinking down and understand what the community values (no surprises!). Folks know about the work we’re doing and can get involved. We understand their needs and concerns and address them. I try to be the voice of the community – as best any one person can – in internal conversations. So we’re as understanding and aligned as a 700+ org of folks, the majority of which are not contributors and are new to this community, can be.

The other big thing I do is help run a community news and event blog called Diff. https://diff.wikimedia.org This is also ongoing, never ending work, that most of the time works well. It’s the more fun, direct work I do in support of the first big thing I mentioned.

The name is super dorky. It’s named after the “differential” view between two edits on a wiki and the difference volunteers make in their work. I get to help share what people are working on from around the world in the pursuit of free knowledge. I’m like the hype man for the Wikimedia movement. Ok, maybe just a hype man, but I love my job and feel very lucky that I get to do this for a living.

In 2022, Diff saw 188,427 visitors making up 386,331 views. We published 640 posts in dozens of languages from close to 300 authors. We have over 720 email subscribers. On the scale of Wikipedia that’s small potatoes (English Wikipedia saw 96 Billion views in 2022), but on the scale of the movement of volunteers – editors, organizers, affiliates, staff, etc. – I’m happy with what we’ve done. For comparison we say we have about 300k contributors across all projects and languages, so to reach 188k “visitors” of that group, and a little beyond, is pretty good in my book.

Diff is very open. You can login with your Wikimedia account and submit a draft. I keep the site running on the software/feature side of things, documentation, and helping review the drafts that come in and answer questions from authors. That last bit takes up a lot of time. I really appreciate everyone who takes the time to write a post and I am here for giving folks the platform and support to share their work.

Here’s a short list of some of my favorite posts this year.

Araisyohei, a volunteer from Japan takes on a behind-the-scenes tour of OYA Soichi Library, a small magazine library in Tokyo. There’s some great photos of their event and an even more amazing video tour of this tiny library embedded in the post.

JA: https://diff.wikimedia.org/ja/2022/06/13/日本随一の雑誌専門図書館でエディッタソンを有/

EN: https://diff.wikimedia.org/2022/06/22/editathon-at-oya-soichi-library-japanese-magazine-library/

Every year Jimmy Wales celebrates Wikimedians for their efforts. Expanded in recent years, the “Wikimedian of the Year” awards are always a highlight. These folks are doing such unique and important work in their free time.

EN (Numerous language selectable in the drop-down): https://diff.wikimedia.org/2022/08/14/celebrating-the-2022-wikimedians-of-the-year/

One of the folks who won an award this year was Annie Rauwerda, from @depthsofwikipedia fame. I was fortunate enough to interview Annie in late 2021, right as she was blowing up. #humblebrag

Her work now has its own Wikipedia article in eight languages!

https://en.wikipedia.org/wiki/Depths_of_Wikipedia

Wikimedians host photo contests throughout the year on various themes. Wiki loves Folklore, Wiki Loves Monuments, Wiki Loves Africa, Picture of the Year, and more. These contests capture the diversity of life on the planet and the amazing talents volunteers have – and share freely. I’m in awe and humbled every time we publish a recap of a contest. Here’s a recent one from the Wiki Loves Africa 2022 contest.

Another from April and the Wiki Loves Monuments 2021 contest.

One of the cornerstones – maybe _the_ cornerstone of what makes Wikipedia work are citations to reliable sources. Access to these sources can be challenging. Many are behind paywalls or in journals that are hard to access. The Foundation helps by building a service called the Wikipedia Library, where volunteers can get free access to these sources to help create and improve articles.

I work with a lot of smart folks who are trying to figure out how to create, sustain, and grow healthy and independent communities. One way we do that is by developing programs, training, and resources for communities to succeed. In this three-part(!) series, Alex Stinson explores how organizing helps the movement grow in relation to our 2030 movement strategy.

Editing an encyclopedia seems like a boring, harmless endeavor. Until you realize that there are people who don’t want this to happen. They don’t like facts. Or laws that could greatly hinder how volunteers can contribute and what we’re able to host. Our legal department and our global advocacy team are some of the most caring, invested folks I know making sure people can express facts – and themselves – in areas of the world where that is dangerous.

https://diff.wikimedia.org/2022/04/20/how-smart-is-the-smart-copyright-act/

We also love to republish articles from elsewhere on the web. Wikimedian and deep learning enthusiast Colin Morris shared his work in trying to discover the _least_ viewed article on Wikipedia.

https://diff.wikimedia.org/2022/06/06/in-search-of-the-least-viewed-article-on-wikipedia/

Last, but not least, our product tames take building software for everyone very seriously. We have a new desktop interface (and I think secretly a new mobile interface too) coming in January. In this post the product manager, Olga a good friend and foxhole comrade, talks about how the web team approaches developing their work with equity in mind. The sort of thoughtful product development we need to see more of in the world.

EN (and seven languages):

https://diff.wikimedia.org/2022/08/18/prioritizing-equity-within-wikipedias-new-desktop/

The Wikimedia movement is messy. People can be jerks and the barrier to entry is far too high for my liking. I show up every day trying to increase awareness and participation of what folks are doing. To gather people together and connect interests and ideas. It’s funny to be working in the blog mines in 2022 – not just working – but thriving when so many folks consider a blog as an old antiquated thing. I think they have a place and more folks should turn to them to share what they are doing and learn from others. I don’t know where I go from here professionally. Something I’ve been talking about with folks, but whatever is next I hope is more of this. Positivity, working together to tell the story of our movement, and supporting one another through difficult times.

Guide for creating 360 panoramas from the DJI Mini 2

About a year ago I got into drone photography with my first drone, a tiny DJI Mini 2. While not the fanciest of drones it does a pretty good job for the price point. Easy to control and decent 4k video.1

One of the downsides is that the onboard software will stitch a 360 degree panorama for you, but only at a lower resolution. The Mini 2 does have a nifty feature to take all 26 photos needed for a complete 360 view, in the DNG format, but it can’t stitch it together for you. So what is a person to do? Enter open-source tools!

I’ve done this a few times and each time I have to remember all the steps. Time to write it all down for myself and if I’m lucky to help others too. 2

Take your photos

First you need to take the photos!

Position your drone somewhere near the object or location you want to take a panorama of. Do not place your drone directly above the point of interest! You want to position the drone away from direct center. It helps make sure your POI gets the best coverage of direct photos. Make sure the drone is between the sun and the point of interest. Don’t have both your POI and the sun in the same direction. You’ll end up with blown out sun flares. I did not do this perfectly with my image above of the Fort, but you can see that the sun is off to the left from where my drone was. You have to learn the rules before you can break them.

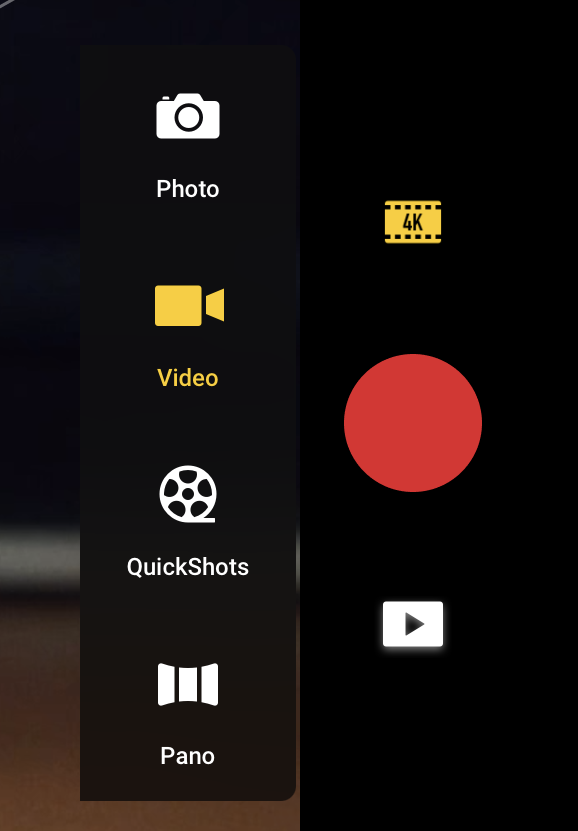

Once positioned, switch the mode to Pano and select Sphere.

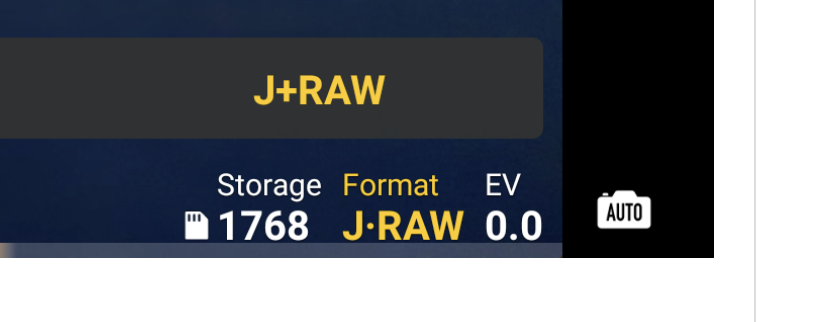

Then make sure your format is set to jpeg + RAW3

Once ready, hit the red record button and let the drone take the photos. It will hover in place and rotate both the gimbal and drone to get as much coverage as possible.

Now you have your drone up in the sky, positioned nicely and you’ve taken some photos. Time to return to the computer. You have a folder of DNGs that are waiting to be stitched together. Enter Hugin.

Hugin

Hugin is an open-source panorama photo stitcher.4 It’s a powerful tool with many knobs and dials. I’m going to focus on the settings that I think are important, but please do read up on all the software can do. I’m doing this all on a Mac, but the interface and steps are generally the same.

Speaking of Macs, the most recent version of Hugin for Mac was last updated in February of 2019. If you’re using a Mac with a Retina (HiDPI screen) display you’ll want to grab a beta release that fixes an issue with Macs with this screen. It’s unfortunately still out-of-date compared to the Linux and Windows releases.

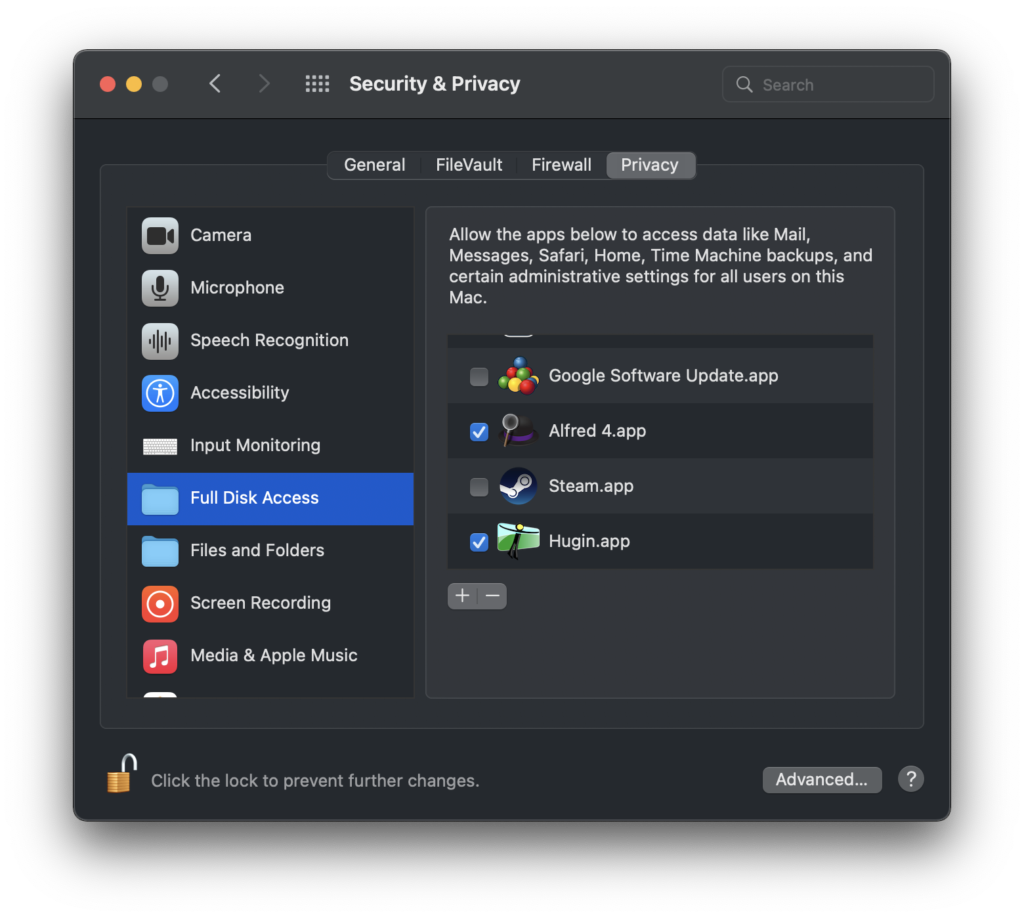

As noted on Hugin’s download section, “On Mac OS 10.15 Catalina and later you will need to manually grant Hugin “Full Disk Access” in the Privacy tab of the OS X System Preferences, Security & Privacy.” Since we’re using an out-of-date and not well supported version of Hugin on the Mac, you’ll want to right-click on the Hugin.app and select Open or else you’ll get a scary warning about it not being trusted (you can trust it). Do the same for PTBatcherGUI.app. You’ll also want to make sure Hugin has Full Disk Access as noted above. Check these settings in System Preferences>Security & Privacy.

Ok, you’ve download Hugin and installed it. The second step done.

DNGs to PNGs

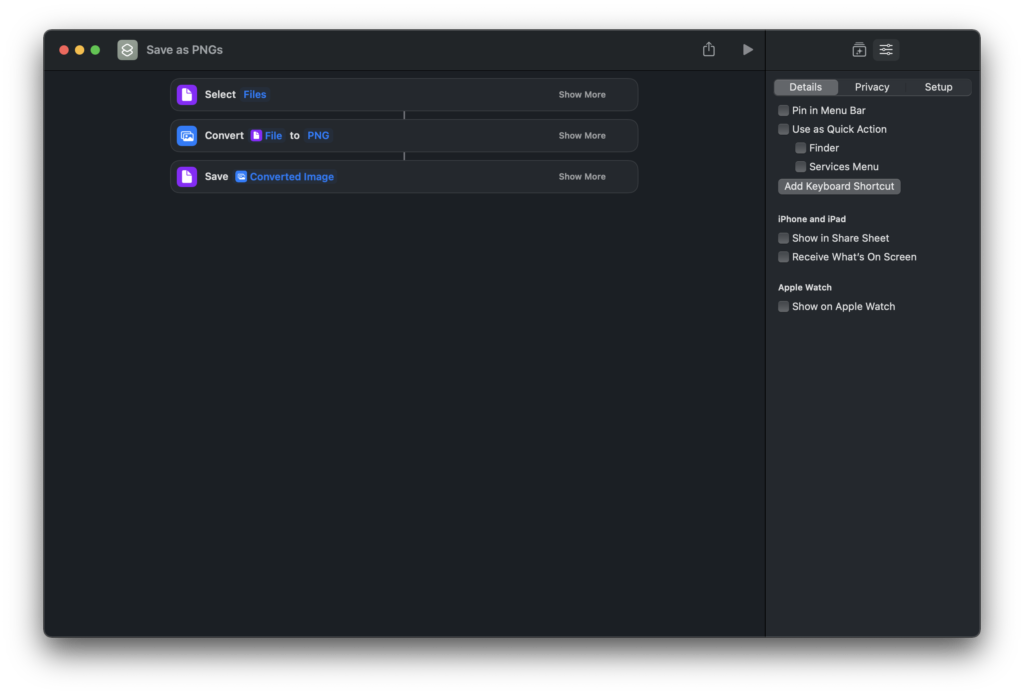

If you’re using the settings above on your Mini 2, you’ll end up with image files in the DNG and JPG formats. We want to use the DNGs as they have more data and less compression. You’ll need to convert them to another format to use with Hugin. You can do this a myriad of ways. If you’re using a modern Mac, a Shortcut workflow to select files and convert to PNG works just fine.

Loading images into Hugin

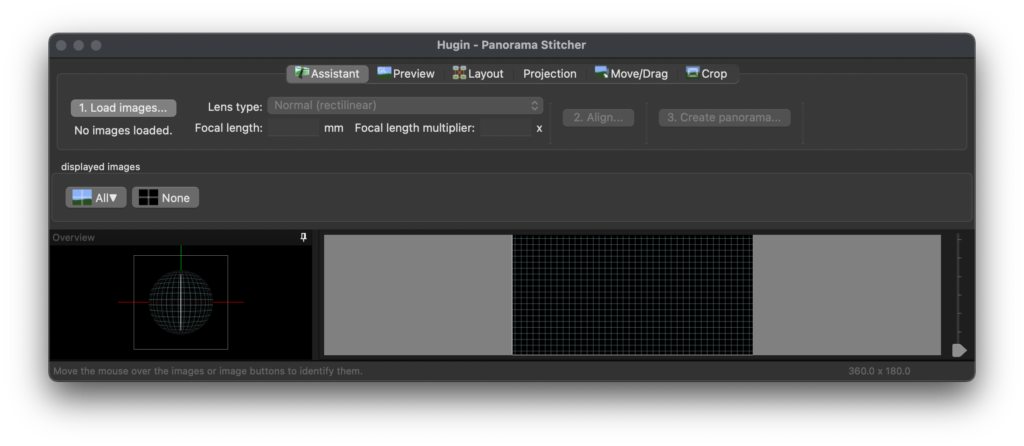

Open Hugin and select Load images… from the main window. You’ll want to Shift+click to select all the PNGs we created earlier.

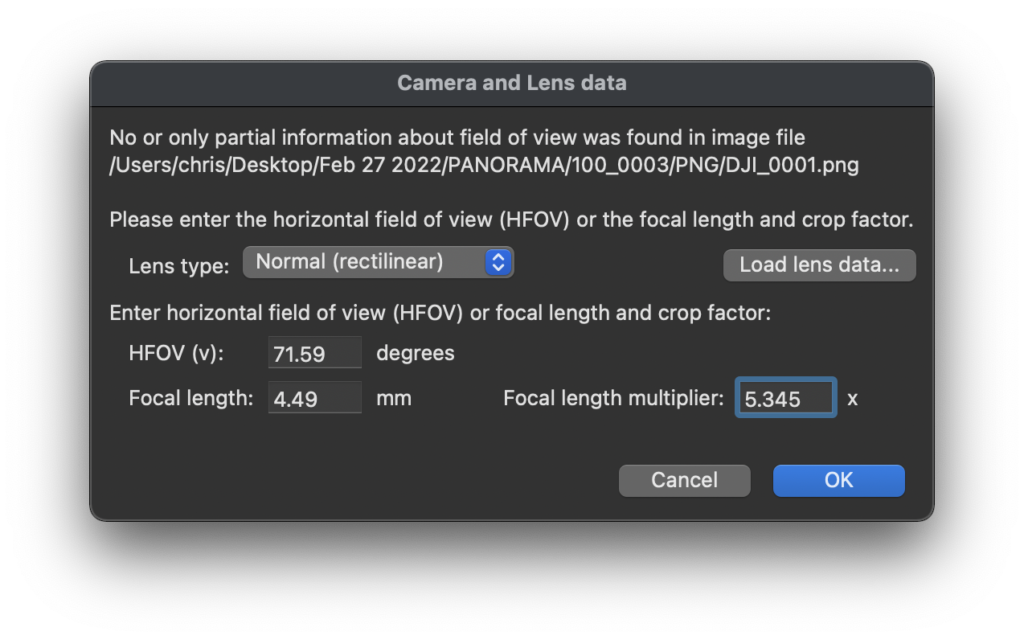

Depending on how you converted the DNGs to PNGS you may be missing the metadata for your lens type. You’ll then see a window asking about the Camera and Lens data. Here’s the settings to use.5

Lens type: Normal (rectilinear)

Focal length: 4.49 mm

Focal length multiplier 5.345 x

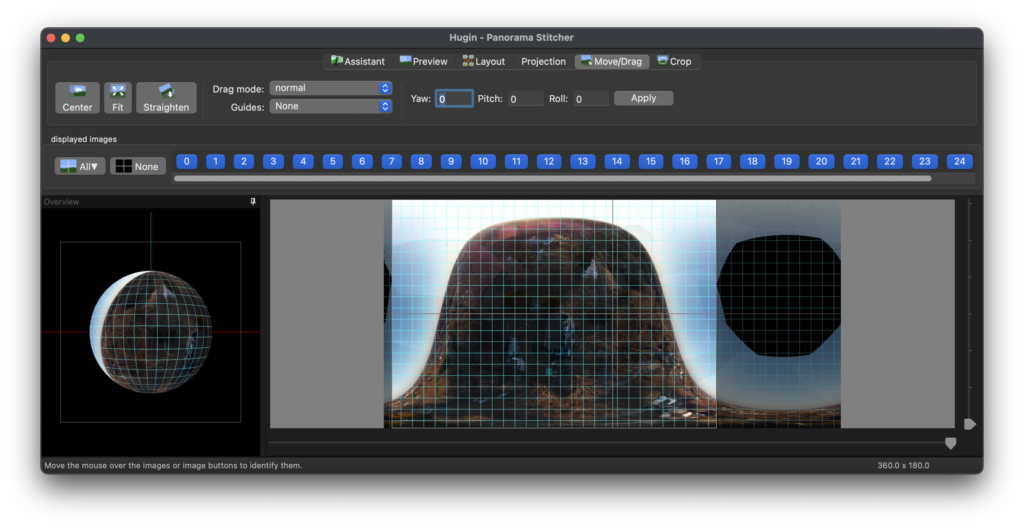

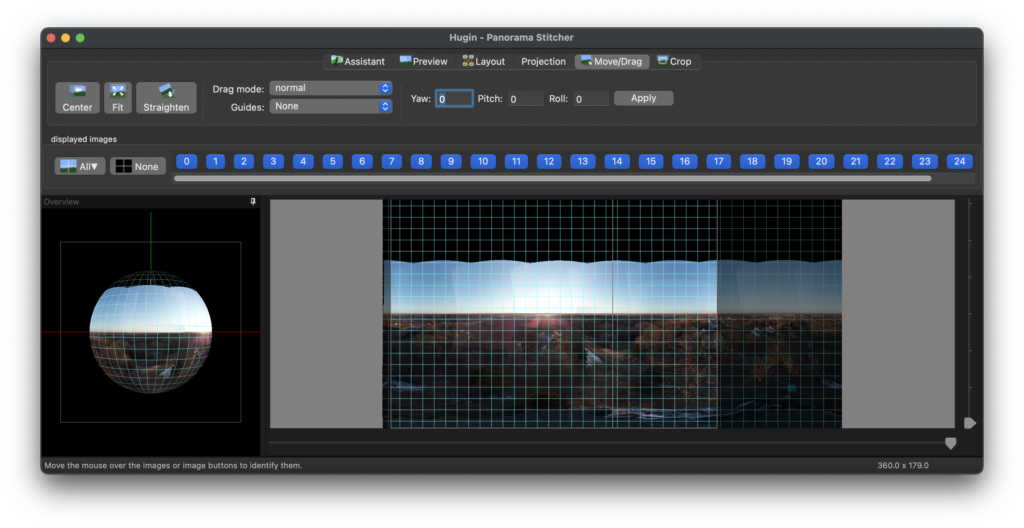

Select Ok. You should see your images in a jumbled mess in the Overview window in Hugin. That’s not right! Click 2. Align… in the main Hugin window.

A new window will pop up and the magic starts. Hugin will analyze all the images and look for points where the images overlap. This might take a few minutes depending on how speedy your computer is. Let it do its thing.

Fine tuning

Once complete, you’ll see something that looks a little more put together. Maybe like a giant ant hill, but at least the sky and ground is consistently attached.

Head over to the Move/Drag option in the main Hugin window. Click Straighten. Hey look, a panorama with a straight horizon and all! Is it upside down? No problem. Roll the image by 180 and click Apply. Click Straighten again for good measure.

Export

Time to tell Hugin to make you a single image. Save your project. Go to File>Save in the menu bar or use the handy command+S to save your project. Head back to the Main Assistant window and select Interface>Expert from the menu bar. “What?”, you might be saying. “I’m not an expert!” Don’t worry. We’re going to use this interface to make a few small tweaks.

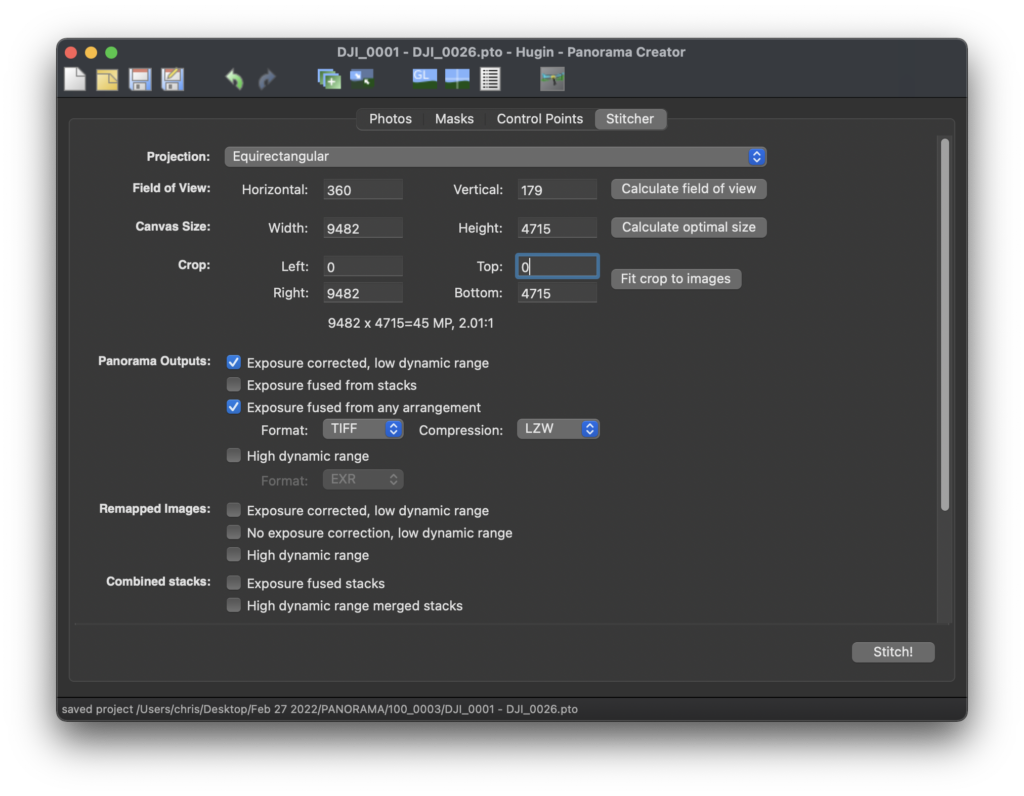

Once the Advanced menu option is selected you’ll see a new window. Select the Stitcher tab.

Form here, make sure the projection is set to Equirectangular. Field of View should be 360 x 180. For Canvas Size click “Calculate optimal size”. The Width, and the Height should be at a ratio of 2:1. So 18648 x 9324, 9482 x 4715, 4096 x 2048, etc. Hugin likes to be helpful and crop out the top of the image where there is no sky (Dones can’t look up!). If you see the Top setting under Crop set to anything other than zero, change it to zero.

I find it helpful to export two versions. One exposure corrected with low dynamic range and the other fused from any arrangement. So I suggest checking the “Exposure fused from any arrangement” option as well.

Hit Stitch! And you’ll be asked to specify the prefix for your images. You can leave this as the default or change it to your liking. Then away it goes! This will take some time.

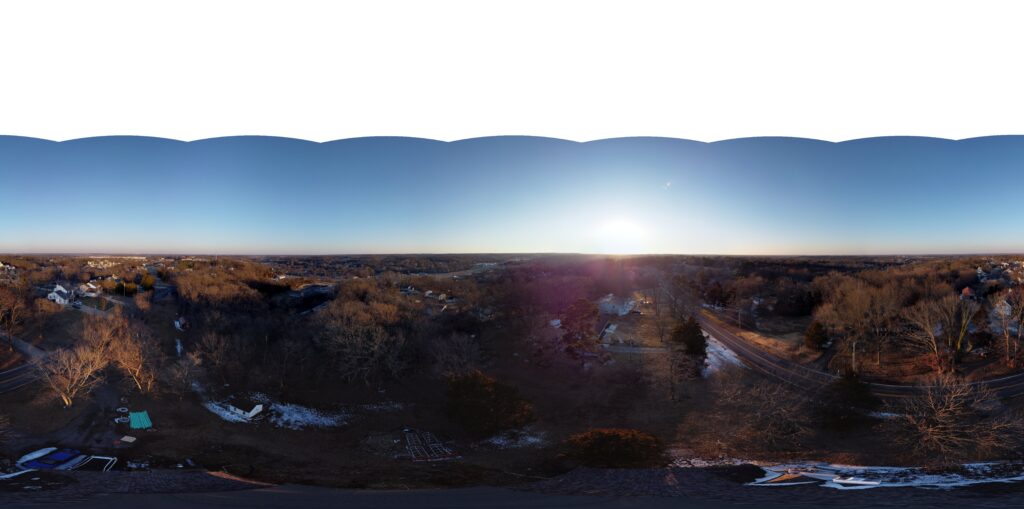

Once complete you’ll have two big TIFF files. By default this will be in the same folder where you saved your project file. One will just have the prefix, the other _blended_fused.

Most times the blended version is the best. These are big files, about 700 MB. If you don’t need/want such a large file, you can always adjust the canvas size in the Stitcher. Just keep the ratio at 2:1.

Take a look at your images. Pick which one you prefer.

Pretty good, eh? All except for the giant void where the sky should be. Time to fix that.

Skyfill

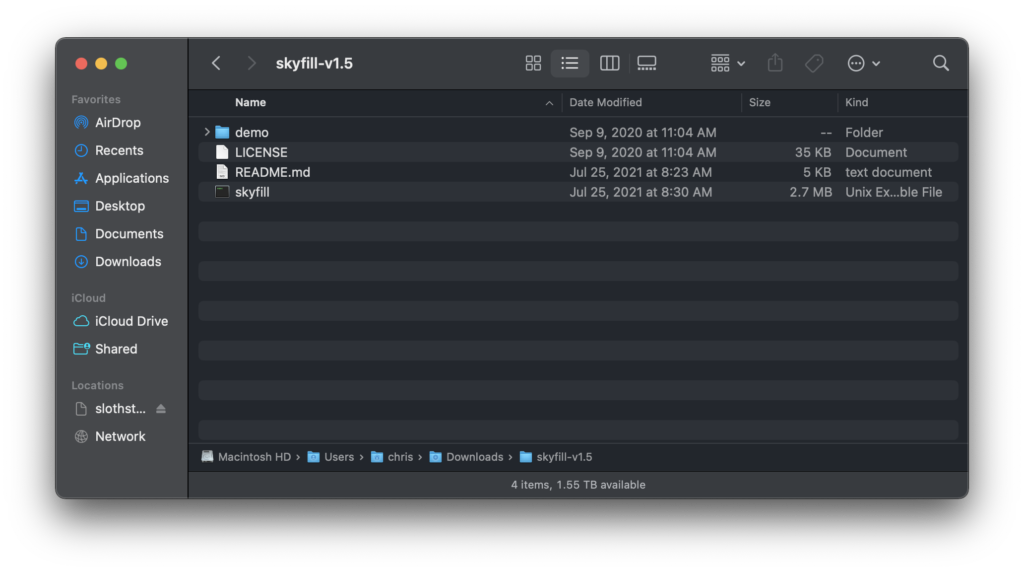

More open-source software! This time we’re going to use a utility called Skyfill to fill in the sky. We can close Hugin for now. Go download Skyfill. There are Linux, Windows, and MacOS (Darwin) versions. Open the zip and inside you’ll see a file called skyfill.

This is a command-line utility, so no point-and-click for this bit. Right-click/control-click on the skyfill file to open it. A Terminal window will open and a bunch of text will appear. You just ran skyfill but with no settings so it will say [Process completed] without actually doing anything. You can close that window. Why did we do all of that? In doing that we did give the program permission to run from the Terminal.

Time to use the Terminal! Open the Terminal app on your Mac by going to Applications>Utilities>Terminal.app. Drag and drop the skyfill file into the Terminal window that appears. You should see something like this.

If you hit return, skyfill will run, but again not do anything. It doesn’t know where the image from Hugin is or what settings you want to use. With the command to run Skyfill still in the Terminal, drag your image to the Terminal window. You should see something like this.

Hit return and skyfill should do its work to fill the sky. The result is a giant TIFF file in the same folder as your source image with the sky filled in. It will have “-filled” appended to the file name.6

So here’s an 360 image where I break the rules when we first began. I have my subject (a house) right below the drone and the sun blaring at the camera. A terrible photo but illustrative of why you shouldn’t frame your photo this way! 🙂

Cleanup

From here you might need to touch things up. Maybe remove an errant bird or adjust the colors. Load the TIFF image into your favorite image editor of choice and go to town. I’m skipping details here because personal preferences differ when it comes to editing software and depending on where and when your image was taken you may have more or less editing to do. Personally I used Pixelmator Pro and do a light pass in editing.

Share

Once you have your image all cleaned up you’ll want to share it with folks. I have a few suggestions and there are other ways to do this.

Flickr

You an upload your image to Flickr as a PNG and the site can display your image in a 360 view. You’ll need to add the equirectangular tag to your image and refresh the page. Here’s an example. You can upload images at large resolutions, but the built-in viewer will downsample them. There is no ability to zoom in on an image.

kuula.co

Kuuala has a nice interface where you can customize the focal point and default view. It accepts photos up to 16384 x 8192 in PNG and allows for viewers to zoom the image.

Google Streetview

If you can get your final image on to a mobile device, you can download the Google Streetview app and upload your photo to Google Maps. Here’s an example of one I created and uploaded.

There are some downsides. Google now “owns” your image and you have very little chance to interact with anyone viewing your images. However, given the reach of Google, many more people can see and enjoy your photos.

Conclusion

This isn’t the perfect tutorial and there may be other tools to help with some of the steps. In my desire to use open-source when possible, this is what worked best for me. If you have a tip or question, please leave a comment. Now go have fun with your sky camera!

A little bit of everything, all of the time

As someone who has been chronically Very Online for many years1 this bit from Bo Burnham’s latest Netflix special really resonated with me. Both for the brilliant and spot-on “ha-ha” comedic description of the modern Internet and the terrifying spot-on oh-this-is-so-tragic synopsis of what the Internet has become and how it impacts us. I’ve watched it at least a dozen times. Content warning: NSFW language.2

via waxy

Using a smartphone as a webcam

I’ve been using my iPhone as a webcam for the last few months. I thought I’d share a few notes here on my experiences for others who might want to try this.

Why use a smartphone as a webcam? Because the “top pick” Logitech webcam on almost everyone’s list is terrible. In fact, in my experience, all webcams are terrible. Mostly because there isn’t much competition in this space so the generational improvements are small.

For example, the top recommended webcam by The Wirecutter up until October 2020 came out in 2012, the same year the iPhone 5 was released! Their latest recommended webcam is basically the same camera with very small hardware differences. The white balance is often off, focus is inconsistent, and the built-in microphones are of the most inexpensive quality you could imagine.1

Conversely, the camera(s) in your smartphone are great and get better every year. Phone manufacturers consistently tout the tech in the camera systems because that’s a huge selling point for these devices. More often than not your most used camera is your phone, right? You probably already have a smartphone too, so one less thing to buy.

So what is the catch? How do I do this magic? I use a free (as in beer) software called Reincubate Camo.2. I install their app on my smartphone. I install their companion app for my computer that runs in the background. It sits here ready to pass the video from my smartphone camera to whatever video chat software I’m using (Meet, Zoom, etc.). A few minutes before my call, I plugin in my phone, launch Camo on my phone and select it as my video input in my conferencing software du jour.

Pros:

- Hands down the best picture I’ve seen (and I’ve used some top-of-the-line telepresence setups by Cisco).

- Consistent, sharp focus on your face, not the bookshelf or wall behind you (I’ve perpetually had this issue with the Logitech).

- Use a device you probably already have (instead of buying another webcam).

- Higher dynamic range and more natural color (see the photos above. You can actually tell there are trees outside my window!).

- You charge your phone while using it. 🙂

Cons:

- Have to install an app on your computer and keep running in the background.

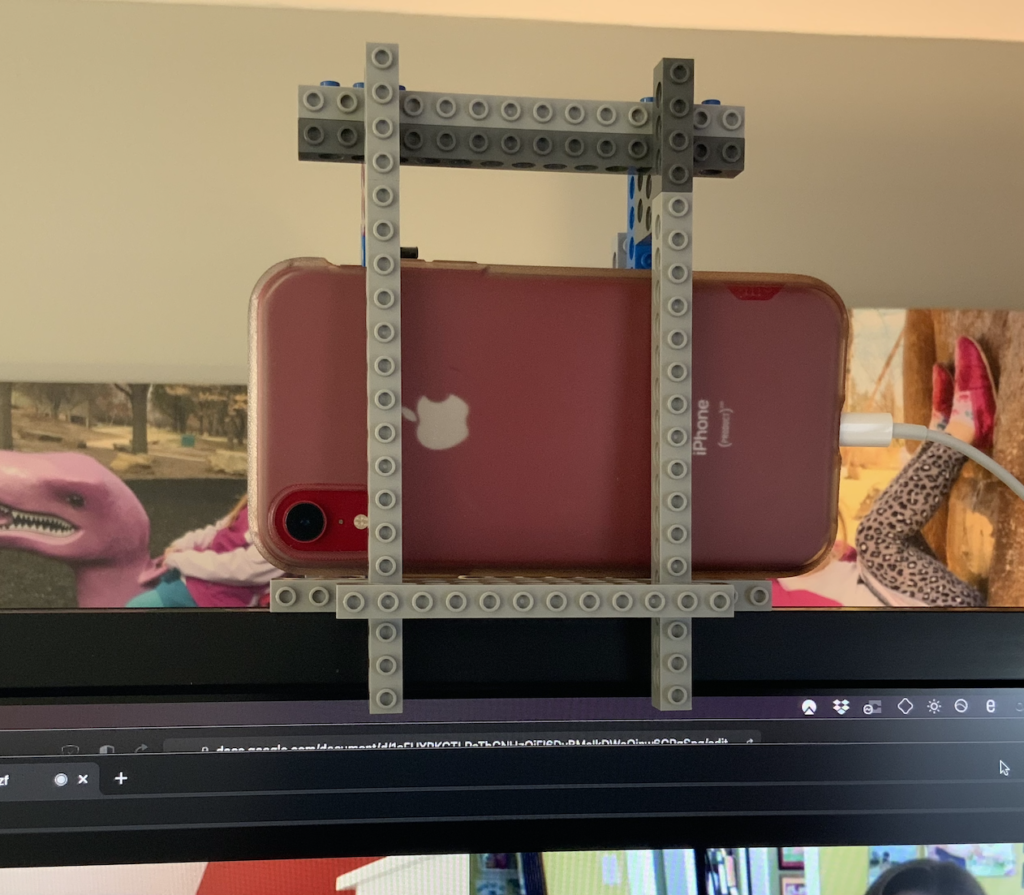

- Need some way to hold phone up at a decent angle. I use Lego (see below).

- Your phone is in use while you are in a call (If you use a 2FA app or something this could be problematic)

- Mac and Windows only

- If you want a resolution over 720p you need the Pro version (but in my opinion image quality is more important than image resolution).

I hope you find this interesting and maybe useful. I’d love to hear about your setup and what improvements you suggest in creating a nice virtual presence.